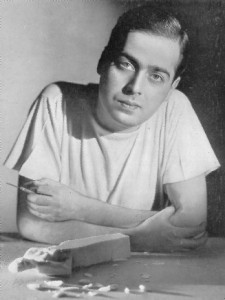

In 1932, Lester Gaba said he packed “a clean shirt and one of my soap sculptures” and headed from Chicago to New York City. He would become a little-known sculptor, seeming to be known and famous only during his own time after he created mannequins for the likes of Saks Fifth Avenue in 1930s New York City.

His passion for window display began when his was a child. His father owned a clothing store, possibly in Gaba’s hometown of Hannibal, Missouri. After his move to New York, he wrote an article in Advertising Arts Magazine and in his self-proclaimed “tirade” he discussed how the imported mannequins used in American department stores did not resemble women in the States. This led to a challenge of sorts from Best and Company, a department store, to create mannequins with more naturalness, mannequins which would encompass the look of the American woman.

These mannequins were called the “Gaba Girls.”

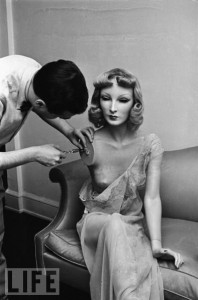

It is unclear who said it, but it was said, by someone, that the mannequins pre-Gaba looked “like human beings who had died and forgotten to lie down.” That changed with Gaba’s Girls. Instead of dead-looking, non-beings of wax or papier-mache, Gaba created mannequins using plaster and fashioned after real women as well as famous women such as Greta Garbo.

Just as dolls have been and continue to be inanimate, yet somehow real, companions of many people from all walks of life, time periods, and cultures, Gaba’s Cynthia became his constant companion.

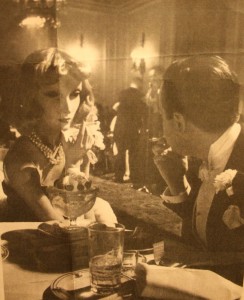

Cynthia, the mannequin he created for Saks Fifth Avenue, enchanted and even startled him in her realism. As a result, he created another in her image all for himself. After this, she became a kind of socialite, attending dinners and soirees with Gaba in 1930s New York social circles. Tiffany, Cartier, and Harry Winston began lending her jewels for her outings with Gaba. She became, then, in a sense, a constant, even living, advertisement amid the very social set who would have coveted such luxuries. She even led an Easter Parade on Fifth Avenue.

Cynthia was the girl of the moment. She was also Gaba’s constant gal.

But all things must end and Cynthia saw her end, for even Cynthia was not immortal. While sitting in a chair in a beauty salon, she fell and shattered into pieces. Gaba said, “Cynthia had become a Frankenstein to me, and I was rather relieved that she decided to — retire.”

I first happened upon this story years ago while working as a Librarian. When assisting a doll-collecting patron, I came upon a book called, Merchants and Traders and turned directly to page 283. That is when I first met Lester and Cynthia. Later, I photocopied the page and held onto to it through my move to Chicago and another move within Chicago. Today, I found it again … or, it seems, it found me.

I always wonder why these things intrigue me. I do know though that most (if not all) things which intrigue me are things from which I can learn. In this story, I learned of a confident man, an almost unbelievably confident (but I do not think narcissistic) man with a pulse on advertising in 1930s America, particularly in New York City.

Unlike Morton Bartlett who was a lonely Massachusetts bachelor who created a “family” out of the dolls he made, Gaba was a social sort. He was out about the town always and was among New York’s most powerful and elegant people. He would take his 100-pound Cynthia with him telling people she was silent because she suffered Laryngitis.

Gaba was quite the wag and I hope his humor and talent lives on. I, for one, am taking a lesson from him about advertising, confidence, and companionship.

Hello Carrie, I’m very curious!!

Do you know if someone owns Lester Gaba’s mannequin?

Or if it’s possible to see them somewhere?

Thank you