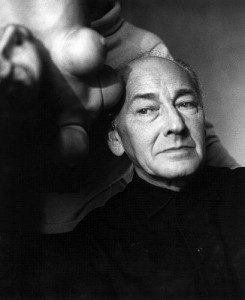

I don’t clearly recall the first time I discovered the artist, Hans Bellmer, but I believe, hazily, that it was in a women’s studies class while I worked on my Master of Fine Arts in poetry. I do recall becoming completely taken with him: imagining him alive, imagining him living daily life as a man, an artist, a person coming to grips with painful memories and unrequited, impossible love.

Born in 1902 in Kattowitz, Germany (now Katowice, Poland), Bellmer grew up with a loving mother and a domineering and angry father. It is possible his relationship with the mother he loved and the father he hated, shaped the artist he would become, an artist who struck even the most surreal of the Surrealists speechless and awestruck.

It was always dark inside of him I think, but doll-making made it understandable.

I caught some grief years ago at a women’s studies conference, “Women and Creativity” at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin where I presented a paper on Bellmer. A full discussion never occurred, instead there were huffs and head shakes making me feel a bit like an outcast throughout the remainder of the conference. One woman raised her hand and asked me how I could sympathize with Bellmer in my paper, “Shock, Awe, and Everything in Between.” As I recall I answered by discussing how I was looking at him as a human being using art as a way to work through pain and confusion. Sigmund Freud, being an influence of Bellmer’s, no doubt facilitated a self-therapy in a sense. I answered that I was acknowledging his need and our need for him, to study him, and I guess I would refer to my “sympathizing” more accurately as having a kind of compassion for a man battling the dark corners within himself.

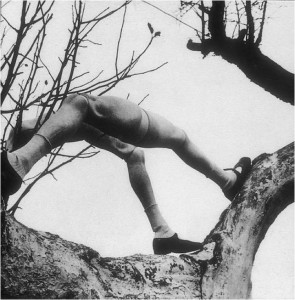

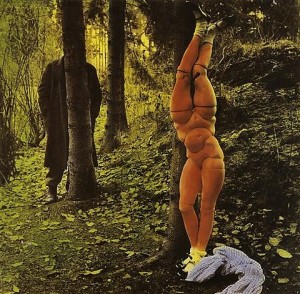

In Bellmer’s book, Little Anatomy of the Physical Unconscious, or The Anatomy of the Image, he writes: “When I am gripped by the sight of a single twisted tree surrounded by others of the same species, which are either twisted differently or not at all, it shows I am receptive to the contorting of the double symbolized by the tree and frees me of my need to contort myself because it is doing so in my stead.”

Like a landscape artist, Bellmer studied the nature around him. He used it, too, in his compositions as the above La Poupee illustrates. Like any truly great artist, he saw and celebrated the similarities of seemingly dissimilar objects. Women are not trees, but Bellmer saw similarities between them: twisted movements, bones and boniness, texture.

He, as a result, is “free” from contorting himself because the double he sees in the tree and the female form contorts on his behalf. It is as if his dolls are performing for him; they are his toys.

There were several catalysts to bring about this work. Bellmer became re-acquainted with toys from his childhood, he read the letters of Oskar Kokoschka (see my post about Kokoschka here), and went to see Jacques Offenbach’s opera, The Tales of Hoffman, a story of an artist named Hoffman falling in love with a doll named Olympia.

Unrequited love was not new to Bellmer.

In love with his cousin, Ursula Naguschewski, Bellmer could not have her, so she became a kind of figure to be studied for his doll sculptures. Later the poet, Unica Zürn would become his figure of study beginning in the late 1950s till her suicide from his window in 1970.

In Kokoschka, Bellmer no doubt saw his own unrequited obsessions with an unattainable woman. For both of these artists, creation and manipulation of the body that represents the unattainable were necessary.

But there is yet another side to all of this, a political one. Actively in opposition to the Nazi regime, Bellmer created his dolls as a way to rebel against the the “purity” the Nazis disgustingly valued at the expense of millions of innocents during the Holocaust. Declared depraved by the Nazis, and disillusioned by the actions happening in his own country of Germany, Bellmer headed to Paris where he would remain.

Meeting the Surrealist artists in Paris, many also exiles from the regime in Germany, his artwork became a sort of muse to the group. They found him intriguing and unique, even a manifestation of what the movement was aiming to uncover and express.

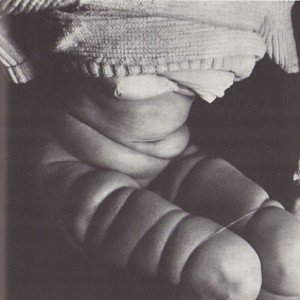

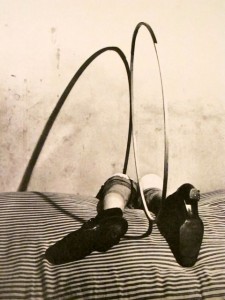

There is so much complexity in his work I have yet to touch upon: the notions of voyeurism and his dolls’ meditation on childhood when innocence is shattered by manipulation.

His dolls often wear little-girl accessories such as Mary Jane shoes, white cotton socks, ribbons. In the above image, the hoop signifies play since it is a toy. From a sculptural standpoint, it adds a dimension with the hoop’s addition of shadow and shape. From a psychological standpoint, she looks failed. Someone has failed her as she lies (face-down if she has a face at all) across a mattress with the hoop no longer being a toy that is its own object, but instead the doll becomes an extension of the inanimate hoop itself.

As far as voyeurism goes, he can watch and not be a part of action. Just as he is not a part of the twisted trees, he is not a part of the dolls’ tableaux. So he watches, learning something about his pain, a loss of innocence while watching the contorted look of destruction in his dolls. He stands in judgment, and, to me, it is not in judgment of women or the female form, but in judgment of himself.

I celebrate Bellmer’s 110th birthday today because he is still teaching us so much about taboo, sexuality, form, desire, pain and how to grapple with these things. He embodies Freudian theory so perfectly I would use him as an example if I were to ever teach a class on Freudian psychoanalysis.

Hans Bellmer, still today, remains a darkest dream.

I have always loved Bellmer’s work and it is great to read an article which mirrors my thoughts and feelings about him as an artist. I’m currently studying him for a personal photography project I am working on and as a previous student of psychology the Freudian symbolism in his images intrigues me. Well done for doing a talk on him in front of so many critics, you certainly have courage!!

Thanks for a great read. x

Long story short, this is a truly a definitive work on a SERIOUSLY under acknowledged artist. His ideas on the hysterical body and even time and dimension from his foreword to a reprint of Die Puppe I own was mind blowing.

As an aspiring artist I look to his works for inspiration as well as I’m a bit of a dollmaker myself. I’m currently working out the details of a doll for a personal photography project and hope to have clay moving soon.

Also I have to commend you bravery on talking about Bellmer to an audience. I once mentioned him in passing while doing a paper in art history about censorship. Though I don’t recall the grade I received. It took guts and I truly admire that.