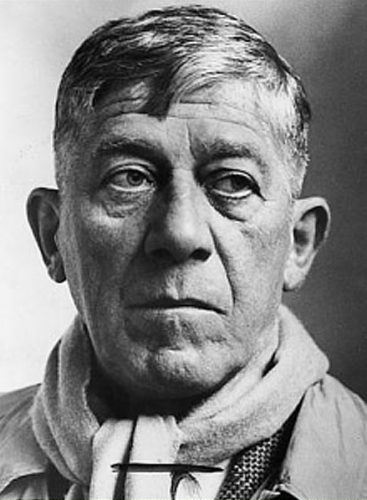

Oskar Kokoschka was a Renaissance man with a pulpy, pulsing passion running through his veins. His passion seems to have been both an intense blessing and a curse. One evening, with red wine overpowering him, Kokoschka beheaded the life-sized doll that could never replace his lost love, Alma Mahler.

After a fiery relationship with Mahler, she suggested years later that Kokoschka should hire dollmaker, Hermine Moos, to create a doll in her likeness so that Oskar would always have her with him.

Kokoschka, who was shot in the head while serving in World War I, became more than just eccentric; by many accounts, he was deemed mentally unstable. His mental instabilities seemed to be part and parcel to his relationship with Alma, as well as the reason for the eventual dissolution of it.

This is an art story of mythic quality. There is proof of the “Alma” doll created by Moos, a doll that Kokoschka did not think captured the essence of his lost love. The doll then became a model for his paintings until her unfortunate demise. The doll was beheaded at a party in front of many other people, party-goers who were no doubt perplexed by the activity.

There is a level of bitter-sweet sweetness to this story. It is sweet that Alma was the inspiration for one of Kokoschka’s most startling and beautiful paintings, Bride of the Wind. Then there is a bitterness in his passive depiction of such a progressive woman.

Alma Mahler was known as a strong and independent woman who happened to be living in a time where she was decades ahead in spirit and personality. I would speculate that Kokoschka’s fantasy of her was to pin her down, pin her down to him. In this painting, his bride is practically swooning taking the pose and post-coital sentiment of a love-soaked damsel in the arms of her virile lover.

So when Alma was gone, Kokoschka took her suggestion and had a life-sized doll made in her image. Of course this doll could not replace her, and as a result, Kokochska went through his remaining years pining for her. She became an obsession that a doll of fabric could not satisfy. Beheading the doll was a way of taking away the doll’s intended identity. No longer was she to be Alma; she was to be nothing, something easily destroyed in a midnight garden.

[…] with toys from his childhood, he read the letters of Oskar Kokoschka (see my post about Kokoschka here), and went to see Jacques Offenbach’s opera, The Tales of Hoffman, a story of an artist named […]